Beyond Point A to Point B: Capturing Human Motion

There is a distinction between movement and motion. The distinction is critical when evaluating human performance. You can measure how far someone moves — point A to point B — but that might not be telling the full story. Motion is different, as it looks into movement on a deeper level — how that movement occurs. For athletes, coaches, and practitioners, this difference can identify injury risk or performance improvements throughout a course of intervention.

Movement vs. Motion

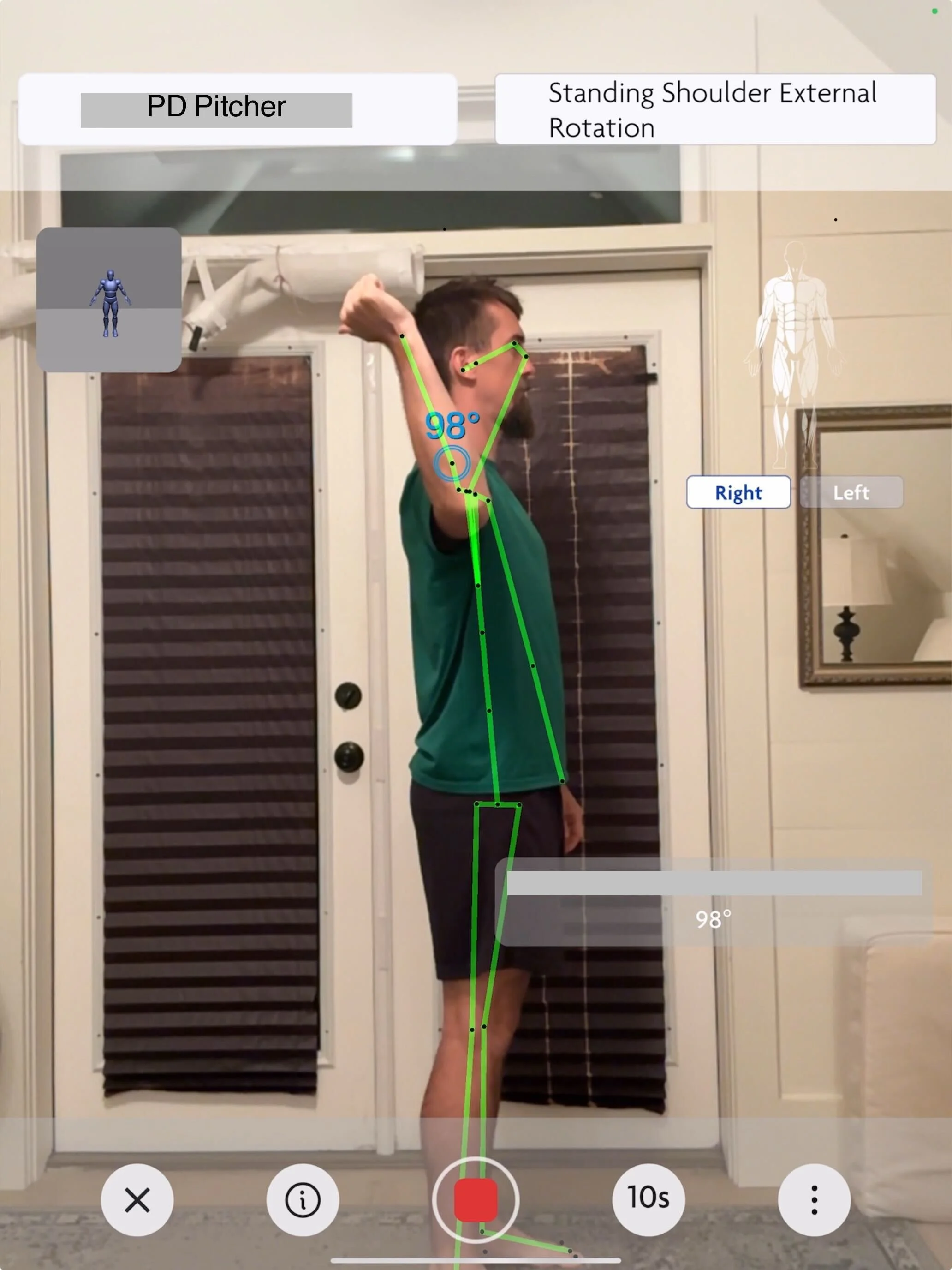

Movement considers the distance from point A to point B, but motion often involves the variation of an object's position relative to a reference point. When capturing human motion, this reference point is often anatomical. It is essential to measure standardized human motions, defined by a fixed arm, an axis of rotation, and a moving arm. KinetikIQ does more than just capture how much movement occurs (from point A to point B), it analyzes motion relative to standard anatomical positions, human motion. Furthermore, rather than just measuring angles in a 2D plane, which is the common practice in sports and physical therapy clinics worldwide, KinetikIQ harnesses 3D LiDAR technology capturing x, y and z-coordinates.

The value of standardization

Standardization is important so that no matter what position an individual is in when the ‘capture’ begins, the data can be compared against other data sets, whether from historical trials of that same individual, or from other individuals. Additionally, this means that motion at different body segments can be compared across tasks, since all are defined by the same three points: a fixed arm, axis of rotation, and moving arm. If only two points were considered, you could not make comparisons between trials without the task being exactly the same, with the starting point needing to be consistent trial to trial. Let’s take an example. When completing shoulder external rotation, a baseball pitcher during preseason may execute rotation by beginning at point-A, and finishing at point-C, where that same pitcher at the post-season may demonstrate a rotational arc from point-B to point-D.

90 degrees is not always the same

To illustrate the point, let’s imagine the intervals (degrees) were the same between all points A, B, C and D, and measuring 45 degrees. Pre-season rotation would be measured at 90 degrees, and so too would post-season rotation. However, the way in which those 90 degrees occurred is very different. In the case of human motion, the stress applied by active tissues and received by passive tissues is clinically and significantly different across these two arcs of motion. While the range of motion is 90 degrees in both cases, the human motion would measure: Pre-season 0 degrees to 90 degrees (90 deg AROM for Active Range of Motion) and Post-season 45 degrees to 135 degrees (90 deg AROM).

In this case example, practitioners would take this information, realize that internal rotation has been lost over the course of the season, while external rotation has been gained, and consider the different tissues at play in order to implement appropriate interventions to address both injury risk and performance.

From data to insights

Analyzing human motion is more than measuring displacement. It’s about understanding and interpreting how movement occurs relative to standardized anatomical definitions. Capturing motion in this way gives practitioners immediate and actionable insights for interpreting injury risk and key performance indicators (KPIs) which drive individualized interventions. With KinetikIQ, practitioners can benchmark, evaluate progress and compare results that enhance performance and protect long-term physical health.

Written by Patrick Dolan, SCCC PhD