Fatigue & the Female Athlete: Part 2

Welcome back! In Part 1 of Fatigue and the Female Athlete, we explored the rapid growth of women’s sport and outlined key physiological differences between female and male athletes.

Summary: Fatigue and the Female Athlete (Part 1)

Women’s sports are experiencing rapid global growth in visibility, viewership, and commercial success, exemplified by record-breaking audiences in women’s soccer and the WNBA. Despite this progress, sport and exercise research remains heavily biased toward male athletes, driven by data availability, financial priorities, and historical sex bias within sports science and medicine. This imbalance limits the understanding of the unique physiological and biomechanical demands of female athletes and highlights the need for female-specific research to improve performance, recovery, and injury prevention.

Physiologically, male athletes typically produce greater absolute power due to higher muscle mass and longer limb lengths. In contrast, female athletes often display greater fatigue resistance, enhanced oxidative capacity, and superior metabolic recovery, linked to a higher proportion of type I muscle fibers, lower glycolytic reliance, and greater fat oxidation. These characteristics are especially relevant given dense competition schedules, as female athletes may not fully recover within 72 hours post-match. Hormonal fluctuations, particularly the role of estrogen and premenstrual hormone withdrawal, may further influence fatigue and recovery responses, underscoring the importance of individualized, evidence-guided recovery strategies for female athletes.

What is Fatigue in the Female Athlete? (Part 2a)

In the context of the female athlete, fatigue is ill-defined. In fact, while reviewing over 40 articles related to fatigue and the female athlete, only three articles explicitly defined fatigue (Nemček & Nemček, 2022, Russell et al., 2019, Temm et al., 2022), leaving the reader to apply their own definition of fatigue.

Most commonly, fatigue can be defined as a multidimensional, reversible reduction in an athlete’s ability to produce or sustain physical and/or cognitive performance, resulting from the interaction of physiological, neuromuscular, metabolic, and psychological stressors and influenced by sex-specific factors such as hormonal fluctuations, energy availability and recovery status (Enoka, 2008, Gandevia, 2001).

More specifically, fatigue in female athletes includes four main areas:

Neuromuscular fatigue: Reduced force or power output due to central (neural drive) and/or peripheral (muscle-level) mechanisms.

Metabolic fatigue: Altered substrate availability, metabolite accumulation and energy system stress, with females often showing greater oxidative capacity and fatigue resistance during repeated efforts.

Perceptual and cognitive fatigue: Increased perceived exertion, reduced decision-making speed and attentional demands.

Hormonal influences: Fluctuations in estrogen and progesterone across the menstrual cycle can modulate inflammation, thermoregulation, substrate use and recovery, contributing to individual variability in fatigue responses.

It is important to highlight that fatigue is task, environment, and individual-specific, shaped by factors such as training load, competition density, sleep, nutrition, psychosocial stress and reproductive health status. Recognizing fatigue as a dynamic and sex-informed construct is critical for optimizing performance, recovery and injury risk mitigation in women’s sport.

Athlete-Reported Measures of Fatigue (Part 2b)

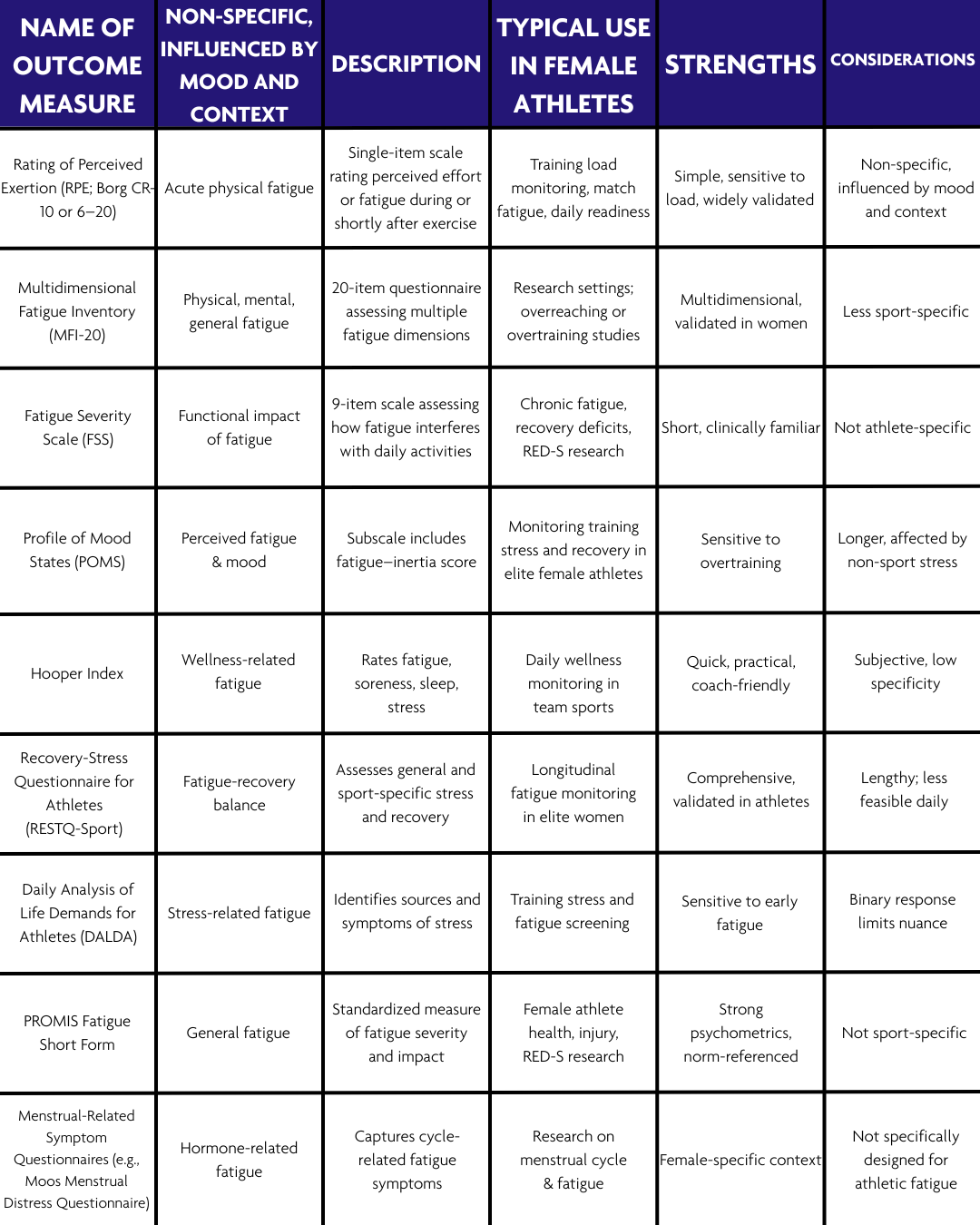

Similarly to the definition of fatigue, athlete-reported measures or tools used to measure fatigue in the female athlete are ill-defined and variable. The most commonly used measures of fatigue are tabled below:

Table describing outcome measures and descriptions

Key Takeaways for Female Athletes Using Athlete- Reported Outcome Measures

No single athlete-reported outcome measure currently fully captures fatigue. Consider the difference between acute (RPE, Hooper) and chronic (MFI, RESTQ, PROMIS) tools.

Hormonal and contextual factors (menstrual cycle, energy availability, psychosocial stress) should be examined when interpreting scores.

Athlete-specific fatigue monitoring benefits from being paired with objective markers (training load, neuromuscular performance, sleep, physiological biomarkers).

What are those objective measures and what are they actually measuring? Stay tuned for part 3- coming soon!